By Azita Agnew

Photo of 19-year-old Anoosh, taken a few months before his execution in 1982 in Tehran, Iran.

The Islamic Republic was established in Iran in 1979 after the downfall of the monarchy, bringing a promise of social justice, freedom, and democracy for all Iranians.

But with the support of the military Revolutionary Guards, the clergy soon excluded all other political allies from the new regime and suppressed anything that they considered to be a Western cultural influence.

The age of marriage was changed to 9 years old for girls, hijab was made mandatory for all women, and men were required to wear modest clothing.

Thousands of young people were arrested, tortured, and subsequently executed in court hearings which lasted only a few minutes and without lawyers present for the defendant.

Anoosh, my 19-year-old cousin, was one of them. He was unexpectedly executed without any announcement to our family. The shocking news of his death was passed on to his mother at the prison through two pieces of paper - his will, and his grave number, “where he could be visited from now on”. His crime, his mother was told, was “waging war against God”.

At the time, we had caring family members with tight ties to the regime who could have stepped in to try to save his life. Instead, they did nothing, believing that the regime’s Supreme Leader was the representative of God on earth and no one should question his actions.

Times have changed, as has the people’s attitude following the death of Mahsa Zhina Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman in September 2022 after she was arrested by the morality police in Tehran.

This photo essay is made up of conversations with fellow Iranian-Kiwis, New Zealanders, and Iranian nationals living in Iran, in their own words. Pseudonyms have been used for Iranian contributors.

Saba holding up her painted hand as a symbolic gesture in protest to the bloodshed in Iran, Auckland, 2022.

“I was 12 and living in Iran when I started studying different religions.

“The core of all these ideologies is basically the same. There’s nothing wrong with religion, it’s got good principles. Where it becomes problematic is when people use it as an excuse to oppress a group, and enforce their beliefs on others. That’s when things get really out of hand, and I could see that in Iran, and I would challenge it.

“I remember asking our morality teacher a set of questions about the origin of the universe. Her response was, ‘it’s a sin to think about that because God’s always watching, so if you question him, you’ll be a sinner’.

“I remember I sat in the classroom and cried - regardless of what you actually do, you’re always going to be a sinner.

“This was our generation. And we had our parents who had recently gone through a revolution. Most of my mother’s friends were executed by the Islamic Republic, so it’s very natural for her to be scared and not want to see her children go through the same horrors.

“But the situation is different now. Iranian Generation Z is fresh, bold, and brave. Our fear doesn’t exist in their young minds. They’re leading this Iranian revolution in the schools and universities, and fighting for a normal life and basic human rights.”

- Saba

Iranian-New Zealander writer & filmmaker, Maza, looking at her freshly inked tattoo, “The revolution is not over”, Auckland, 2022.

“I didn’t teach my boys about being Iranian … because of one single word: ‘shame’.

“It was shameful to be Iranian for so long. And it came from society telling you to be shameful of what you are. When you have been mistaken for your government, the government that you’ve always been against... to be cast into one category as that government whilst not realising that we are the people that suffered at the hands of that regime.

“I did not want that shame to be passed on to my kids. That shame wasn’t my fault; it’s not a child’s fault when they go to a Western country as an immigrant and they get told to shut up because they’re a terrorist. It’s not a child’s fault for developing that shame.

“As an adult now, I feel shame for not teaching them about Iran. And I can fix that now. I can tell them that they should be proud to have Iranian blood… It’s important that they understand what’s going on in Iran right now.

“We’re not victims, don’t get me wrong for one second. I do not victimise us. I’m just saying it as it is. That was the reality of us and it’s made us stronger. That’s why Iranian women are now kicking ass like this. We’re not gonna give up until we win, and we will win. The question is not whether or not we win, the question is what happens after we win.”

- Maza

Iranian school girls in their uniforms in the streets of Shiraz, Iran,1997. The provider of this photo wishes to stay anonymous.

“I was in middle school when they invited top students to go for a visit to our local ‘Mobilisation of the Oppressed’ organisation.

“I had no idea what the invite was about, or where we were going. They didn’t force us to go. They came to our class, called our names, and asked us to get our stuff and go with them.

“Over there they asked us to report our classmates to the organisation if they used makeup, or if they had girlfriends or boyfriends. They asked us to report our friends if they said things that seemed anti-regime.The report should be in the form of a letter to the Mobilisation of the Oppressed, they said. They literally asked us to be traitors, to betray our friends, and turn them in.

“After that day I stopped having any relationship with those friends that were there with me in the meeting. I couldn’t trust them anymore. I was scared of them. Because although I never reported anyone, how could I be sure that my friends wouldn’t?”

- Hope

Avishan performing in an Iranian protest rally, Aotea Square, Auckland, November 2022.

“It breaks my heart to see that many Iranian girls can’t have the type of freedom that we have here in New Zealand.

“Here, we are free to think for ourselves, and make a lot of decisions on our own. We can choose what we wear, including clothes that symbolise our ethnicity. I know that Iranian girls want to express themselves freely, and have the same basic rights as we do here without being punished for it.

“When I left Iran, we came here to be safe, and to be free. I know I am blessed to be in New Zealand. No one can lay hands on a woman here. But in Iran, they can, and they can get away with it.

“I used to be really ashamed to be recognised as an Iranian girl. Because when I went to school here in New Zealand, I was called ISIS. So I would say that I was born here. But I always felt guilty about it.

“When I got older, I realised that I wanted to be a voice for Iranians in situations like this because Iran is my home, it’s my birth country … and you know, it will always have a special place in my heart. I had to put the shame aside, and try to change my perspective, and I did. I am now proud to say I’m an Iranian woman.”

- Avishan

Wendy performing in an Iranian protest rally, Aotea Square, Auckland, November 2022.

“As a Kiwi, I’ve been into activism all my life from a young age. One of the first things that I went through emotionally when I started to learn about what has been happening in Iran is that my government, my media, my school, my everything has let me down. Because I’ve lived through these last 40 years and I didn’t know. And most people with a little bit of empathy would be pretty fucking pissed off, I reckon, if they understood this situation.

“That beauty of Persia that was and still is, Iran, is lost because from out here, the world only sees ‘Islamic Republic’ every time they see a Persian. It is because of this picture of Iran that we’ve been force fed for so long through media exposure and education.

“The Islamic Republic has controlled everything and made it so restrictive that we can’t see any beauty. The beautiful art of design in Iran that has been around for thousands of years is now lost in the world. And it’s all because of the way that these motherfuckers used a religion and twisted it to control everybody by controlling the woman.”

- Wendy

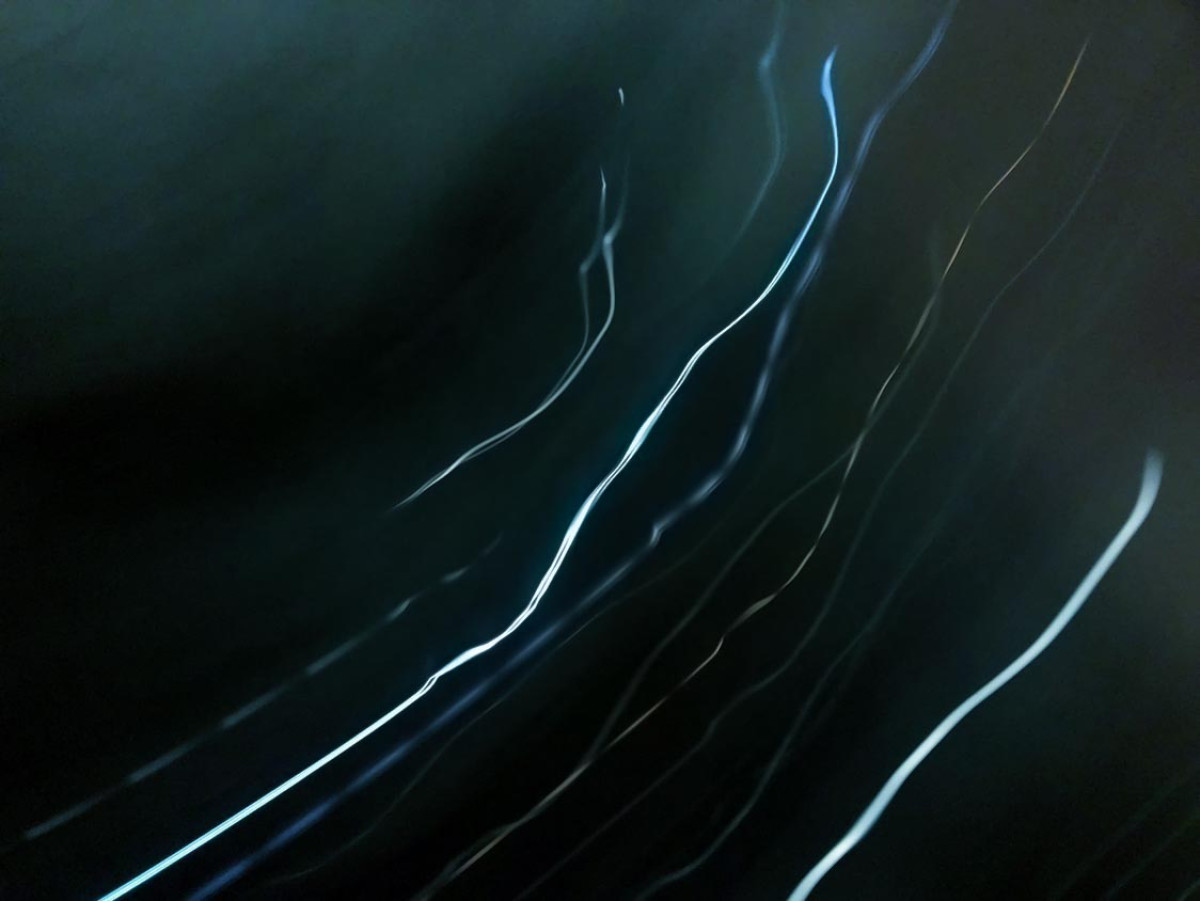

“I took this with my phone. The liberation of movement floating in the depth of darkness closely represents my world today.” - Ordinary Citizen, Tehran, 2022.

Three accounts of everyday life in Tehran, December 2022:

Day one: “I’m on my way to work. The security forces, armed with heavy weapons and batons, stand in groups on each street corner. Acting as food deliverers, plain clothed police take snapshots of people and watch their every move. A few of the state’s billboards have been burnt down by the protesters the night before. My elderly cab driver is quietly crying. The plain clothed police have snatched his 20-year-old son in the middle of the night from his home.”

Day two: “Everyone is busy at work when all of a sudden a crying young man who has recently joined our group passes me by. Later I hear his 18-year-old cousin has been shot dead in the street. The security forces have confiscated the dead body, and taken his family into custody. We never see the young man back at work again.”

Day three: “The football team has beaten Wales in the World Cup. In a large square in the centre of the city, the black-clad guards with heavy weapons and batons dance on top of anti-riot vans and wave their flags. Other armed men scare away the terrified passers-by so no crowd is formed. Tehran’s air is the most polluted it has been in a while. The rainless and snowless winter slowly starts in Tehran.”

- Ordinary Citizen

Persian/NZer human rights activist, Mahsa, with her son, Auckland, 2022.

“I never viewed myself as an activist until a couple of months ago in September, when the ‘woman, life, freedom’ movement started happening in Iran.

“I left Iran in 2004, as an outspoken, independent young woman. I didn’t believe Iran would be free of the Islamic Republic in my lifetime. But then I started seeing what was happening in Iran. And the thing that really got under my skin was the crimes against children.

“I am a Mum, I think about my own two kids, I think about my own childhood during the Iran and Iraq War, and how much that has impacted me as a person, still paying for it decades later. To see these parents burying their children and then seeing the bravery of them continuing to fight for freedom, for change …

I felt that I couldn’t live with myself in the future if this was happening in Iran and I did nothing.

“No parent should be burying their child because their child refused to sing a pro-regime song at school.

I don’t care which country or which regime it is. This should not be happening in a world that we are living in right now, in 2022.

“As Gandhi said, ‘be the change you wish to see in the world’. I can’t sit here and be infuriated about things and do nothing about it. So yes, I am an activist, a human rights activist, and a children’s rights activist now. And I have made a pledge to myself that I will do everything I can until I see an end to this gender apartheid regime in Iran.”

- Mahsa

Golzar holding the daisies from her father’s garden in Orumiyeh, Iran, 2018. Photo provided by Golzar.

“As for my own experience as a Kurdish-Iranian woman, I remember when I went to university in Iran,

my parents were quite concerned. They told me that I should be more careful than others because I was a woman, a Kurd, and also a Sunni Muslim (a religious minority group in Iran). I’m not religious but I was raised as a Sunni.

“They told me I belong to three groups that are considered by the Islamic Republic to be highly dangerous, and if I did something wrong, my mistake would be met with a much more brutal consequence - and that is true.

“Whenever the fascist regime in Iran wants to create fear among people, they arrest some Kurds or Sunnis, label them separatists, then execute them. It’s a narrative that they can easily sell to justify their violent existence as the shepherds of the people.

“I’m not a separatist. I love Iran so much that I feel emotional now talking about it.

“I was offered a PhD in mechanical engineering in Turkey, but I went back to Iran, to my family and friends. I wanted to study in my own country. Then when things became worse and worse in Iran, I decided to leave again. I ended up coming to New Zealand for my PhD studies. I will go back to my homeland when it’s safe - I can’t wait to go back.” -

- Golzar

Rob and his wife at their family home, Auckland, 2022.

“It’s really, really tough. The mornings, I think, are the most difficult times, because as New Zealand wakes up, there’s been a lot of activity, protests, and killings overnight in Iran. And I see my wife in the morning, checking her phone, making sure that her family is okay.

“It’s quite challenging, because in New Zealand we have the freedom to express ourselves; to

protest, and to feel safe - particularly with the police and government. And to see our freedom here compared to what’s happening to the amazing people of Iran is heartbreaking.

“I’ve been quite fortunate to have travelled to Iran a few times. My wife and I had our wedding in Shiraz; such a special place. Iran is an incredible country to visit with the warmest people I have ever met. I have two children who are half Iranian and I want them to be able to visit Iran one day and see their heritage - to see what an amazing country and culture they have come from.

“The Iranian regime is operating as a terrorist organisation throughout the world. They need to be called out for what they are. The precedent has been set with the sanctions against Russia and that needs to happen for Iran too. As a New Zealander, I want to see our government on the right side of history and make sure that they’re getting into action, now, this year.”

- Rob

Iranian-Kiwi criminal lawyer and activist, Samira, addressing the crowd at an Iranian protest rally, Queen Street, Auckland, December 2022.

“Our prime minister, as part of her press conference on October 31, mentioned that we do have sanctions in place here in New Zealand for the Iranian government, which I found rather appalling and misleading.

“What we currently have in place in New Zealand are the US trade sanctions that unfortunately only affect Iranian citizens, not the Iranian government.

“The sanctions are supposedly designed to put pressure on people so they pressure the government - but methods like this don’t work in a non-democratic country like Iran where people have no influence on the government’s decision making. These are the sanctions that our prime minister actually talked about. So it was rather strange to say such a thing in a public forum, because these sanctions have zero effect on the vicious Iranian regime, their military Revolutionary Guard and their money that is used for operating a worldwide terrorist organistaion.”

- Samira

Mahsa’s tragic death was reported by all major news agencies around the world and was considered to be a crucial moment for women’s rights in history. Auckland, 2022.

Mahsa Zhina Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman was detained by the morality police in Tehran

for not wearing her hijab properly. Mahsa was reportedly beaten, fell into a coma and died a few days later in hospital on September 16, 2022.

Her death was the catalyst for a women-led mass protest which sparked a revolution amongst Iranians from all ages, genders, ethnicities and religions. People joined together in demonstrations and strikes, demanding a fundamental change in the country’s governing body where their basic human rights are respected.

The protests have been met with a violent crackdown by the regime's security forces. More than 500 people, including 69 children, have been killed and several hundred injured. People have been shot for simply honking their car horns in support of protesters, or targeted while innocently passing by the demonstrations.

More than 18,400 have been arrested, some raped or tortured, and are currently awaiting their sentencing. The Iranian parliament has issued a letter signed by the vast majority of members calling for harsh punishments of protesters.

The first known execution was conducted on December 8, 2022, where 23-year-old Mohsen Shekari was sentenced to death “for street obstruction” in a sham trial without due process. He was executed less than three weeks after his sentencing. Five more people have been sentenced to death only days after Mohsen’s execution, with Amnesty International warning of the risk of further bloodshed.

More stories:

‘It’s not safe for us’: Indian NZers on the rise of the far-right

The community is concerned a Hindu supremacist ideology is growing in Aotearoa

'Modern day slavery': How Aotearoa treats seasonal workers

The current treatment of seasonal workers breaches eight different human rights.

It's a fucked up world. That won't stop Gen Z from trying to make it better

In the face of so many challenges, what keeps young people fighting?