If a person spends more than 13 weeks in hospital, their benefit is automatically cut to $55 a week. Some patients and advocates say it’s not enough to survive on and the automatic process further punishes people who are too unwell to fight it.

Rhiannon Purves has been bedridden in Wellington Hospital for months. Her entire life is confined to four walls as she is unable to walk and is hardly able to speak.

The 34-year-old’s days consist of tossing and turning in a bed and desperately finding ways to distract herself from chronic pain and exhaustion.

“It’s like dying but you’re still here, and an end to the suffering never comes,” she told Re: News journalist Zoe Madden-Smith over email.

Rhiannon suffers from Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), a long-term illness that causes extreme fatigue, problems with thinking and sleeping, dizziness and pain.

She could only be interviewed via email because even a phone conversation leaves her exhausted.

Rhiannon Purves has been in hospital for over 13 weeks due to ME/CFS. Photo: Supplied.

“You grieve constantly for the loss of the life you had, the future you wanted, and who you used to be,” she says.

Now, after spending more than three months in hospital, Rhiannon has been told her supported living payment of $480 will be reduced to $55 a week.

Rhiannon wasn’t aware of the “hospital rate” until she woke up one day to an email warning her it would come into effect in four weeks.

She says the shock of this and how hard it has been to contact and hear back from Work and Income has caused severe ongoing stress which has caused her health to deteriorate further.

“I won't survive here on $55 per week,” she says. “It's not enough to cover my medication alone.”

Benefits can be cut during long stays in hospital

Regional commissioner for Social Development at the Ministry of Social Development Gagau Annandale-Stone told Re: News if a person is in hospital for more than 13 weeks, their benefit will be reduced to their “hospital rate” which is $55.35 a week (after tax). Unless the person has a partner and a child or is a veteran.

“The hospital rate is intended to cover the costs of personal items. All other costs associated with Rhiannon’s health are the responsibility of the health provider.

“If the hospital is unable to fund medications she needs, we would require verification from a health practitioner that they are essential for her condition, and provide reasons why the hospital cannot pay these costs.

“Rhiannon may be entitled to a higher rate of payment but we would need details of her financial commitments.”

The Ministry of Social Development website says "if the hospital rate isn't enough to cover your costs [such as rent, mortgage, insurance], we may be able to pay more. This will depend on what expenses and income you have while you're in hospital."

Rhiannon filled out the form on their website that lists her costs while in hospital, however, she didn’t hear back from anyone and her benefit was cut.

‘There needs to be a conversation first’

Beneficiary advocate Kay Brereton says the decision to significantly reduce someone’s benefit amount, particularly someone who is disabled and in hospital, shouldn’t be automated.

“That needs to be something that is explored by a case manager in depth beforehand to find out what their situation is. Are you going to be staying in hospital? If you leave, will you be going into the same accommodation? Are you paying rent or a mortgage while in hospital? What other costs do you have?

“We need a case worker to work through all of these things before a benefit is changed, a computer can’t do that. It can’t just be an expiry date.”

Brereton says there can be an assumption that when you are in hospital, everything you need is there.

“But it’s not,” she says. “Things like podiatry, haircuts, doctor visits, hygiene products, phone bills, subscriptions, additional food or medication, they have to pay for all of that out of a small allowance of $55 a week.”

“The idea behind this is ‘[the government] is already taking care of you completely, so we are not going to give you the same amount of money’. Despite the fact that they knew before you went into hospital, you had these really high disability costs.

“I personally don't think anyone's benefits should be switched off without a conversation.”

‘Impossible’ to reach Work and Income

Since receiving the email on January 27 that said her benefit would be cut, Rhiannon worked with her case manager to send Work and Income information about the costs of her medications and appointments that are not covered by the hospital.

Some of these costs involve unfunded medications which cost $200 every one to two months, appointments with an osteopath, physio, online consultations with a ME/CFS specialist in New York, as well as supplements and electrolytes for her nutritional deficiencies.

Her case worker delivered this information to a Work and Income office in Wellington and requested a review on February 14, this information was also sent via email. But she heard nothing back, and two weeks later her benefit was cut.

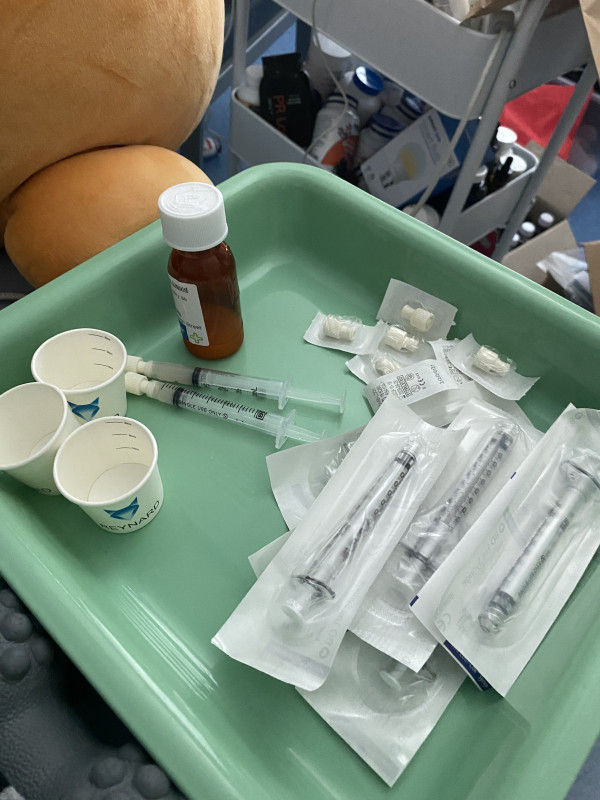

Rhiannaon’s hospital treatment. Photo: Supplied.

Rhiannon says Work and Income is aware she is not able to speak on the phone but they have not contacted her via email either.

After several calls and emails between Re: News and the Ministry of Social Development, regional commissioner Annandale-Stone confirmed it “received an application from Rhiannon, via her hospital support worker, on 14 February 2025, requesting a higher rate of payment to meet her medical costs”.

“We accept we could have responded in a more timely way and explained to Rhiannon what additional detail we need. We appreciate that this has caused Rhiannon stress.”

Annandale-Stone stated more documentation was needed from a health professional about why the medications “are essential for her condition, and provide reasons why the hospital cannot pay these costs”.

In response to this statement, Rhiannon said: “I did send them my disability form signed by my doctor which verifies the costs I have, but they’ve continued to ignore that. They really like to make you jump through hoops.”

‘The process isn’t accessible for disabled people’

Rhiannon says the struggle to get in contact with Work and Income for three weeks while being unwell has been exhausting and frustrating and shows the automated process is not viable for disabled people who are in hospital.

She says it should not have to take “countless” emails from herself, her case worker, and a journalist as well as a formal complaint to get a response.

Rhiannon Purves in hospital. Photo: Supplied.

“They’re making it impossible to contact them. It should not be this hard for a disabled person in hospital to get help. It’s stressful and hard for patients who are so sick.”

‘Very little support’ for New Zealanders with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, says advocate

There is no known cause or cure for ME/CFS, so care usually involves treating the symptoms that most affect a person's life.

The debilitating illness can last for years and sometimes leads to serious disability and can make it extremely hard for someone to keep a job, go to school and take part in family and social life.

Vanessa Atkinson, the general manager of ME support, a support service for people with ME/CFS, says it’s estimated over 45,000 New Zealanders are affected, which is four times more than those with Parkinson’s Disease.

“The number of affected people is rapidly expanding due to Long Covid with around 10-20% of people who had Covid-19 going on to have Long Covid,” she says.

Despite this, Atkinson says there is “very little support” in the public health system for people who have ME/CFS or Long Covid in “heartbreaking situations” like Rhiannon.

“Unfortunately Rhiannon’s situation is not unique amongst our community and it is not uncommon for the Ministry of Social Development to change benefits without talking to the client first.

“This is challenging for anyone, but for those severely ill with ME/CFS or Long Covid it can be devastating as the debilitating nature of their illness means they do not have the energy or time to try and get their benefits reinstated. This is grossly unfair and puts already physically and financially vulnerable people at greater risk.”

More stories: