Māori are underrepresented when it comes to the medical field.

Māori doctors make up 4.7% of doctors in Aotearoa, according to research done in 2023 at the University of Auckland.

But Māori patients are 43% more likely than non-Māori to be in hospital with healthcare complications, according to a study done in 2023 at the University of Auckland.

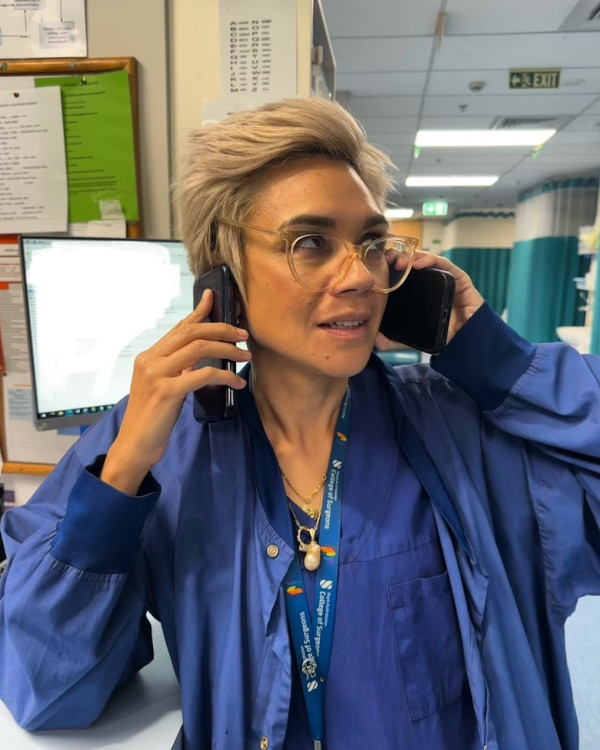

Re: News spoke to Māori doctor Emma Wehipeihana (Ngāti Tukorehe, Ngāti Porou) about why the representation of Māori doctors is important and how she can connect with patients through te ao Māori.

Emma Wehipeihana. Photo: Supplied.

Why is it important to have Māori doctors?

It is important to have a medical workforce that reflects the population that it serves. It improves patient care and has the potential to influence decision-making at every level of the health system to deliver equitable healthcare for all.

What jobs or roles do Māori doctors have that non-Māori doctors don't have?

‘Cultural loading’ is a concept that is well documented with regards to Indigenous doctors.

This is when you are expected to undertake unpaid work simply because you are Māori.

Examples include being an on-call translator, being asked to perform token karakia at meetings, offering advice on research protocols to fulfil “Māori engagement” criteria, and being expected to speak for all Māori on issues.

This is most commonly seen on committees where there is a single Māori doctor included to offer the “Māori perspective” without support of a tuakana or peer; this leads to increased potential for burnout, feelings of isolation and, always, the worry that you’re not qualified enough to undertake the task of fixing everything that’s wrong for our people with your one voice.

I will caveat this explanation by saying that many of us feel that it’s a privilege, and part of our reason for entering the medical workforce, to provide a Māori perspective and advocate for our people. I work with some awesome non-Māori accomplices (not allies) who are equity-focused and work with integrity, who I love supporting in this way.

However, when it is tokenistic and imposed by those who aren’t working in partnership with you, it is exhausting and demoralising. There are still so few of us in the medical profession, and there are fewer the more senior you become, so it is very easy for our Māori doctors to become disheartened and feel alone.

There is support - Te Ohu Rata o Aotearoa, our Māori Medical Practitioners Association provides opportunities for us to be together and share trauma/collaborate on kaupapa.

Like all Māori organisations, they are underfunded and under-resourced and, with the workforce shortages we are experiencing, it’s not always easy for us to get leave to attend hui.

There are other international conferences that I try to get to every other year, the Pacific Region Indigenous Doctors Congress (Pridoc) and the Leaders in Indigenous Medical Education (LIME) which are wonderful opportunities to share mātauranga with Indigenous doctors from other whenua.

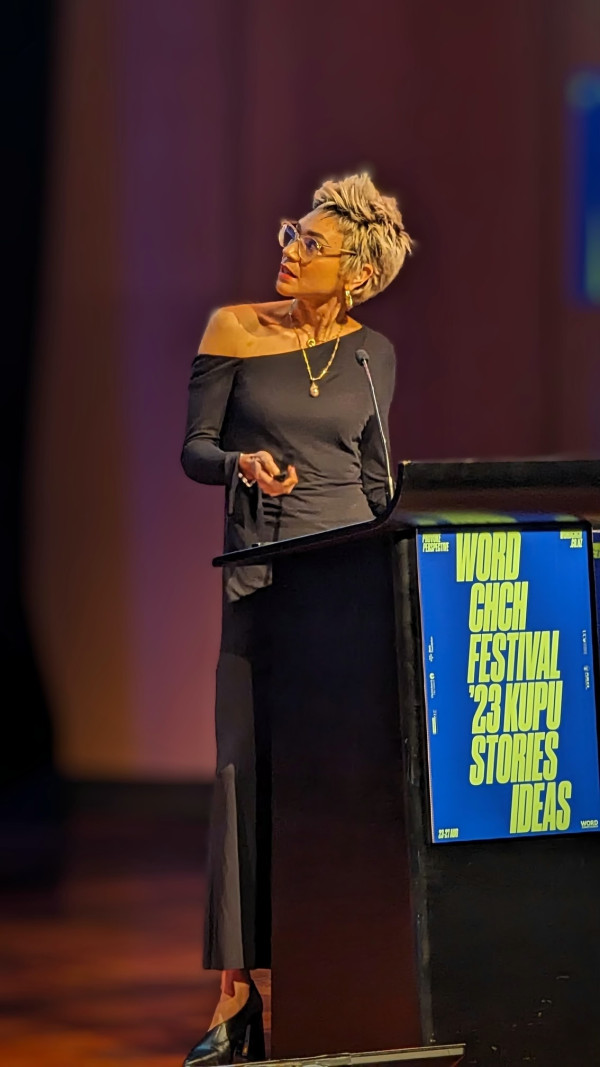

Emma Wehipeihana. Photo: Supplied.

What is it that makes Māori and other diverse doctors so important on the frontline?

I’m fortunate to work in a team who come from a variety of ethnic backgrounds, and it benefits our patients enormously in terms of the therapeutic relationship, to be looked after by a doctor who looks like them, who understands what’s important to them and their whānau.

Quite often patients will tell me that I’m the first Māori doctor they’ve ever met. I appreciate being able to be there for them, but I’m sad that people get to their 50s or 60s without ever meeting a Māori doctor.

We also cross-pollinate - by this, I mean that in a diverse workforce, people feel safer to be able to be themselves in their authentic cultural identity, and this also builds the capability and understanding of those around them.

Would it help if we had more?

Yes, and it’s hard to achieve due to the time it takes to train doctors. We have nowhere near a representative number of Māori doctors relative to the population currently.

This is why the leaders who initiated the Māori and Pacific Admissions Scheme and The Mirror on Society at Auckland and Otago universities’ medical schools, respectively, were so visionary in establishing these programmes.

They are social justice initiatives created in part to correct the inequities experienced by Māori due to structural racism that is built into our society.

It’s tiresome to reiterate the facts over and over again for those who insist everyone starts from an equal playing field, but for the slow learners, these are many such examples in our history, for anyone who cares to look.

These include policies like the Native Schools Act which diverted Māori education away from the curriculum offered to non-Māori, which in effect was social engineering designed to push Māori into labouring and domestic services careers.

It includes the State-initiated, calculated theft of land, resources and suppression of culture and language.

People who have lived with the privilege of being ignorant of these issues either in their own lives or the lives of Māori around them, simply should not be able to insist that they don’t exist.

Especially when they don’t bother to learn the history of this country.

For people who say race doesn't matter when it comes to medical care, what's your response to that?

I would love it if ethnicity didn’t matter when it comes to medical care.

Unfortunately, the evidence, the mountains and mountains of scientific evidence tells us that it does.

Even if you were content to blame Māori with the old, tired, mantra of “poor choices" for our own reduced life expectancy and worse health outcomes compared to non-Māori, you would have to be intentionally ignorant of the good quality studies into all the many ways that the health system fails Māori specifically.

This is a violent and dangerous line to pursue, and it harms our people by even voicing it.

You work in the Middlemore emergency department - what does a day/night in the life of a Māori doctor look like?

I’m a non-training registrar in general surgery. That means I’m not on a formal training programme yet, and I work with house officers, a senior registrar and several consultant surgeons on a team.

We often have students from the medical school as well. We start the day early and leave late. This is because our hospitals all over the country are chronically busy, understaffed, and under-resourced.

An average week is a mix of things. I might be admitting new patients in ED, assisting with an elective operating list, or seeing patients in the clinic.

Our patients tend to be very sick, with lots of what we call comorbidities - other illnesses which make their treatment more complicated. These are things like diabetes, smoking-related lung diseases, high cholesterol, high blood pressure and many other diseases that we know disproportionately affect Māori.

Operations become more risky when people have these comorbidities, and our patients who need surgery to fix conditions like appendicitis, gallbladder disease or cancer, need multi-disciplinary team care to ensure they have the best possible outcome.

Emma Wehipeihana. Photo: Supplied.

How does being a Māori doctor help you understand your patients? Does it make it easier?

There are aspects of being a Māori doctor - our reo, understanding of tikanga and other things that are intrinsic to our identity, which help with whakawhanaungatanga (the process of establishing relationships) which is beneficial to our patients.

More importantly, I think what we want to achieve is an environment where our Māori doctors are empowered to bring their full selves to mahi every day.

I mean our clinical expertise, but also ensuring that the settings in which we practice empower us to practice as Māori doctors, not just doctors who happen to be Māori.

More stories:

Why NZ needs more Māori and Pasifika blood donations

"To give someone the ultimate koha and keep his memory alive is the greatest tribute."

Our clothes are a walking protest

“It’s a really amazing way as an artist to have a travelling canvas that is cruising the streets.”

How kura kaupapa Māori work

A former kura teacher shares her thoughts.